Designing for Actor Based Systems

Many people are intrigued and excited about Erlang style concurrency. Once they get the capability in their hands though they realize that they don’t know how to take advantage of the capabilities processes or actors provide. To do this we need to understand how to decompose systems with process based concurrency in mind. Keep in mind, that this material works equally well for actors in Scala or agents in F#. Differences between actors and processes don’t much matter for the sake of this discussion. Before we dive into process based design it will be helpful to look at a more familiar approach so we can contrast the two.

If you come from an OO background your natural instinct is to design much like you do when decomposing a problem for OO programming. After all, processes are much like objects in that they send messages to one another and they hold state. It goes something like this

- Determine your use cases

- Create a narrative of what it is you are trying to design

- Run through the narrative and pull out the nouns as potential classes

- Do the same for the verbs acting on the nouns as potential methods on the classes

- Clean all this up getting consolidating any duplication

For example, lets say you were trying to build software to run a vending machine. The use cases might be paying for and getting a soda. Another one might be paying too little and getting change back. So one of the narratives there might be

As a customer I put sufficient coins into the vending machine and then press the selection button for coke and then press the button to vend and the robotic arm fetches a coke and dumps it into the pickup tray. The coke is nice and cold because the cooling system keeps the air in the vending machine at 50 degrees.

Now we think about all the unique nouns in our narrative which are: customer, coins, vending machine, selection button, coke, vend button, robotic arm and cooling system. And we generally turn them into objects. Next we consider the verbs that act on those nouns and consider them for methods.

selection button : push

vend button : push

robotic arm : pickup (coke)

etcetera… After this you apply some lovely object oriented design principles and voila - you have a system that nicely models your narrative but does not take advantage of more than a single core on your system and is positively undistributable.

Oh come on you say, don’t be daft, substitute the word object for actor and you are good to go. Well as it turns out not quite. Do we really need a coin process, how about a vend button process and lets not forget the coke process?? Darnit, this makes no sense! Lets back up and see what we can do about this.

Designing for Process Based Concurrency

The first thing you must do before we move on is say this three times

“Processes are not threads. Processes are really cheap. Ohmmmm”

“Processes are not threads. Processes are really cheap. Ohmmmm”

“Processes are not threads. Processes are really cheap. Ohmmmm”

This trips up folks new to process bases systems. They want to be stingy with processes worrying that they will take a long time to create, have massive context switching times, pollute L1 cache, etc… Remember that in almost all such systems, certainly for Erlang, Scala and F# processes/actors/agents are green threads. This means they have their own schedulers built into the VM they are running in. You never have to swap out a thread to switch between running one process vs another. With Erlang based systems you usually configure one erlang scheduler per core on the system. These schedulers remain relatively constant.

With that in mind we solve some of the sticking points many new to process based systems have; not taking advantage of all the concurrency in the system or using complex “process pooling”.

One process for each truly concurrent activity in the system.

That is the rule. Going back to our vending machine what do we have that is really concurrent in that system. Coins? Not really. Slots? Not really. Buttons? Not really. Those are not activities they are things. What are the truly concurrent activities, the activities that do not have to happen in synchronous lock step?

- Putting coins into the slot

- Handling coins

- Handling selections

- Fetching the coke and putting it into the pickup tray

- Cooling the soda

We can use a process for all of these activities. We don’t If you want to name them for the nouns that perform the activities - but remember we are not making them processes because they are nouns. Notice how we go granular here, we did not just create a process for the customer and the vending machine. We created one for all the truly concurrent activities in our narrative - in this way we leverage more of the concurrency available to us. Now we know what processes we need, the next step is to organize them.

Organizing Processes

The various languages that use process based concurrency have differing levels of sophistication here. I am going to draw on the concepts from the Erlang language which have been used in the Akka system for Scala and which I have rolled successfully myself in F#.

Again, forget all of your OO modeling techniques. Processes are not objects, they are fundamental units of concurrency. Forget all your thread modeling techniques - it’s not even close. Share nothing copy everything changes the game. To get started think about which of your processes have to cooperate with one another. In this case what do we have.

- Putting coins in a slot, cooperates with

- Handling coins, cooperates with

- Handling selections, cooperates with

- Fetching the coke and putting it into the pickup tray

and nothing cooperates with, Cooling the soda - it happens whether or not other processes are there to support it or not. Putting coins in the slot however makes no sense if there is no way to handle them, and handing them makes no sense of you can’t make a selection and making a selection… well you get the drift.

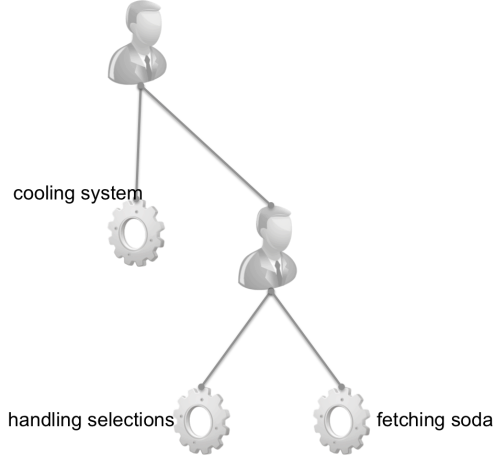

To model this we are going to use a tree of “Supervisors”. Supervisors create and watch over processes. Because of copy everything share nothing properties of actors one can’t corrupt another. So, a supervisor can watch over an actor and restart it when it blows up in the presence of some error. This means we get some incredible fault tolerance. But, that aside, lets talk about how to model these dependencies. We do so in a tree. First, we setup a supervisor at the top of the tree which models no dependencies between any of the processes it starts. In this layer we add the cooling system and then we add another supervisor which will start the group of dependent processes in the order in which they depend on one another. This supervisor will restart processes that die according to their dependencies. If a dependency dies the supervisor will kill and restart dependent processes so that everything starts in a known base state down the chain.

**

Now with things decomposed into processes, dependencies fleshed out and placed into a supervision hierarchy you are basically ready to go. Is there more to design for actor based concurrency - yes of course there is but here you have the fundamentals. Now it’s time to go and play with it and generate questions. Feel free to ask them here or on twitter at @martinjlogan. I may do a second installment on some more advanced topics based on feedback.

If you want to learn more come to Erlang Camp Oct 10 and 11, 2014 in Austin!

**

**